|

LRS NewsletterThe Library of Renaissance Symbolismwww.libraryofsymbolism.com “Moreover, if for the administration of the sacraments, certain symbolisms are drawn, not only from the heavens and stars, but also from all the lower creation, the intention is to provide the doctrine of Salvation with a sort of eloquence, adapted to raise the affections of those to whom it is presented from the visible to the invisible, from the corporeal to the spiritual, from the spiritual to the eternal.” St. Augustine | ||||||

| |||||||

THE PHYSIOLOGUSThe Physiologus, which is usually translated as “the Naturalist”, was one of the most widely circulated books of the Middle Ages. Originating as a Greek text in Alexandria probably during the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the anonymous author drew on the descriptions of animals by earlier Greek and Roman authors and deduced a moral from each description. It was soon adopted by the Church as a vehicle for simple moral or spiritual teaching. Over the centuries it was translated into most European languages including Latin, Icelandic, Armenian and Ethiopian and as time went on, the text was expanded and it became the forerunner of the medieval Bestiary. Such was its popularity that it has been said that the Physiologus singlehandedly set back the development of the natural sciences as we know them by 1,000 years. The Bestiary can be distinguished from the Physiologus by the expansion of the number of animals treated, the addition of images and a change in tone from spiritual to moral interpretations of the symbolic message.

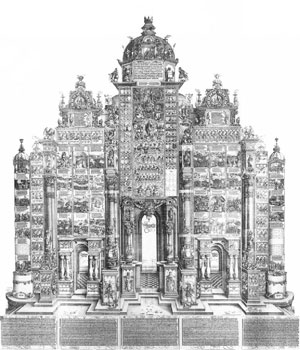

The original version of the Physiologus was anonymous but later it was ascribed to various authors including St. Epiphanius Bishop of Cyprus in the 4th century CE and it was this version that became the first printed Greek edition of the modern era. The editio princeps of 1587 by Zanetti and Rufinelli in Rome was immediately followed by the 1588 edition of Plantin in Antwerp. Both editions were edited by Ponce de Leon the cubicularius, or personal assistant, to the Pope and both editions describe just twenty animals in 25 chapters. De Leon says he used three manuscripts to prepare the edition but these were so debased that he had to omit eleven chapters altogether (the original Greek version had between 40 and 48 chapters). Sbordone in his classic exposition reviews seventy-seven mss. of the work but is nevertheless taken to task by Perry who shows that Sbordone missed several of the critical ones including the earliest one in Greek from the 10th century which is now in the Morgan Library as Morgan 397. The edition of 1587, a print copy of which is in the Library of Symbolism, has woodcuts by a contemporary Italian artist and the 1588 edition has copper-plate engravings by Pieter van der Borcht. This latter edition is fully described here. Each chapter of these editions has a Description and Interpretation in Greek with a Latin translation and Notae or commentary by de Leon

Both the Physiologus and the Bestiary took their place with the other books of animal symbolism of the Renaissance: the Beast Epics (such as the Roman de Renart), the Volucaries (such as Jean de Cuba’s Jardin de Santé) and Emblem books (such as Camerarius’ Symbolorum & Emblematum Centuria, a Century of Symbols and Emblems). The encyclopaedic Historia Animalium, the History of Animals, by Konrad Gesner, is often reckoned to be the first modern work of zoology, but even here each of his descriptions was prefaced with a symbolic interpretation of the animal he was describing. The last part of this vast tome was published in 1587, that is contemporaneously with de Leon’s Physiologus although in his list of sources Gesner describes this latter as by an 'author obscurus'. The Physiologus was finally reprinted in 1618 in Nicholas Caussin’s De Symbolica Aegyptorum Sapienta (On the Symbolic Wisdom of the Egyptians) although Caussin’s enthusiasm for the text was apparently limited. His commentary is confined to just one of the animals described. | |||||||

Bibliography: Fr. Sbordone, Physiologus Rome: Albrighi, 1936; Alan Scott The Date of the Physiologus in Vigiliae Christianae, 52, 4 (Nov., 1998), pp. 430-441; Michael J. Curley Physiologus: A Medieval Book of Nature Lore University of Chicago Press, 2009; B. E. Perry Physiologus ed. F. Sbordone in American Journal of Philology 1937, 58. | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

Future editions of the Newsletter will contain: Stories from the first English edition of Poggio’s Facetiae; Epigrams hidden in a 16th century manuscript; Fables and the Lives of Aesop; Rebuses in the 16th century; All about Enigmas; And much, much more. | |||||||

Contributions of text to the Newsletter, including Articles; Reviews, Notes or Events or contributions of bibliographic material to the Library are welcome and will be properly acknowledged in their place. For how to contribute see www.libraryofsymbolism.com/ | |||||||